Cormac McCarthy, último premio Pulitzer por su novela

The Road, es uno de los mejores escitores estadoundenses en activo (almenos, el único que no publica sólo por seguir la costumbre). En su vida ha ofrecido dos únicas entrevistas. Ésta es una de ellas.

"You know about Mojave rattlesnakes?" Cormac McCarthy asks. The question has come up over lunch in Mesilla, N.M., because the hermitic author, who may be the best unknown novelist in America, wants to steer conversation away from himself, and he seems to think that a story about a recent trip he took near the Texas-Mexico border will offer some camouflage. A writer who renders the brutal actions of men in excruciating detail, seldom applying the anesthetic of psychology, McCarthy would much rather orate than confide. And he is the sort of silver-tongued raconteur who relishes peculiar sidetracks; he leans over his plate and fairly croons the particulars in his soft Tennessee accent.

"Mojave rattlesnakes have a neurotoxic poison, almost like a cobra's," he explains, giving a natural-history lesson on the animal's two color phases and its map of distribution in the West. He had come upon the creature while traveling along an empty road in his 1978 Ford pickup near Big Bend National Park. McCarthy doesn't write about places he hasn't visited, and he has made dozens of similar scouting forays to Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and across the Rio Grande into Chihuahua, Sonora and Coahuila. The vast blankness of the Southwest desert served as a metaphor for the nihilistic violence in his last novel, "Blood Meridian," published in 1985. And this unpopulated, scuffed-up terrain again dominates the background in "All the Pretty Horses," which will appear next month from Knopf.

"It's very interesting to see an animal out in the wild that can kill you graveyard dead," he says with a smile. "The only thing I had seen that answered that description was a grizzly bear in Alaska. And that's an odd feeling, because there's no fence, and you know that after he gets tired of chasing marmots he's going to move in some other direction, which could be yours."

Keeping a respectful distance from the rattlesnake, poking it with a stick, he coaxed it into the grass and drove off. Two park rangers he met later that day seemed reluctant to discuss lethal vipers among the backpackers. But another, clearly McCarthy's kind of man, put the matter in perspective. "We don't know how dangerous they are," he said. "We've never had anyone bitten. We just assume you wouldn't survive."

Finished off with one of his twinkly-eyed laughs, this mealtime anecdote has a more jocular tone than McCarthy's venomous fiction, but the same elements are there. The tense encounter in a forbidding landscape, the dark humor in the face of facts, the good chance of a painful quietus. Each of his five previous novels has been marked by intense natural observation, a kind of morbid realism. His characters are often outcasts -- destitute or criminals, or both. Homeless or squatting in hovels without electricity, they scrape by in the backwoods of East Tennessee or on horseback in the dry, vacant spaces of the desert. Death, which announces itself often, reaches down from the open sky, abruptly, with a slashed throat or a bullet in the face. The abyss opens up at any misstep.

McCarthy appreciates wildness -- in animals, landscapes and people -- and although he is a well-born, well-spoken, well-read man of 58 years, he has spent most of his adult life outside the ring of the campfire. It would be hard to think of a major American writer who has participated less in literary life. He has never taught or written journalism, given readings, blurbed a book, granted an interview. None of his novels have sold more than 5,000 copies in hardcover. For most of his career, he did not even have an agent.

But among a small fraternity of writers and academics, McCarthy has a standing second to none, far out of proportion to his name recognition or sales. A cult figure with a reputation as a writer's writer, especially in the South and in England, McCarthy has sometimes been compared with Joyce and Faulkner. Saul Bellow, who sat on the committee that in 1981 awarded him a MacArthur Fellowship, the so-called genius grant, exclaims over his "absolutely overpowering use of language, his life-giving and death-dealing sentences." Says the historian and novelist Shelby Foote: "McCarthy is the one writer younger than myself who has excited me. I told the MacArthur people that he would be honoring them as much as they were honoring him."

A man's novelist whose apocalyptic vision rarely focuses on women, McCarthy doesn't write about sex, love or domestic issues. "All the Pretty Horses," an adventure story about a Texas boy who rides off to Mexico with his buddy, is unusually sweet-tempered for him -- like Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer on horseback. The earnest nature of the young characters and the lean, swift story, reminiscent of early Hemingway, should bring McCarthy a wider audience at the same time it secures his masculine mystique.

But whatever it has lacked in thematic range, McCarthy's prose restores the terror and grandeur of the physical world with a biblical gravity that can shatter a reader. A page from any of his books -- minimally punctuated, without quotation marks, avoiding apostrophes, colons or semicolons -- has a stylized spareness that magnifies the force and precision of his words. Unimaginable cruelty and the simplest things, the sound of a tap on a door, exist side by side, as in this typical passage from "Blood Meridian" on the unmourned death of a pack animal:

"The following evening as they rode up onto the western rim they lost one of the mules. It went skittering off down the canyon wall with the contents of the panniers exploding soundlessly in the hot dry air and it fell through sunlight and through shade, turning in that lonely void until it fell from sight into a sink of cold blue space that absolved it forever of memory in the mind of any living thing that was."

Rightful heir to the Southern Gothic tradition, McCarthy is a radical conservative who still believes that the novel can, in his words, "encompass all the various disciplines and interests of humanity." And with his recent forays into the history of the United States and Mexico, he has cut a solitary path into the violent heart of the Old West. There isn't anyone remotely like him in contemporary American literature.

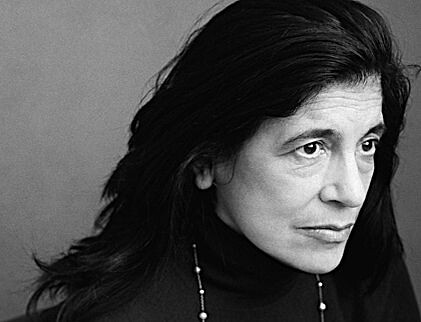

A compact unit, shy of 6 feet even in cowboy boots, McCarthy walks with a bounce, like someone who is also a good dancer. Clean-cut and handsome as he grays, he has a Celtic's blue-green eyes set deep into a high-domed forehead. "He gives an impression of strength and vitality and poetry," says Bellow, who describes him as "crammed into his own person."

For such an obstinate loner, McCarthy is an engaging figure, a world-class talker, funny, opinionated, quick to laugh. Unlike his illiterate characters, who tend to be terse and crude, he speaks with an amused, ironic manner. His involved syntax has a relaxed elegance, as if he had easy control over the direction and agreement of his thoughts. Once he had agreed to an interview -- after long negotiations with his agent in New York, Amanda Urban of International Creative Management, who promised he wouldn't have to do another for many years -- he seemed happy to entertain company for a few days.

Since 1976 he has lived mainly in El Paso, which sprawls along the concrete-lined Rio Grande, across the border from Juarez, Mexico. A gregarious recluse, McCarthy has lots of friends who know that he likes to be left alone. A few years ago The El Paso Herald-Post held a dinner in his honor. He politely warned them that he wouldn't attend, and didn't. The plaque now hangs in the office of his lawyer.

For many years he had no walls to hang anything on. When he heard the news about his MacArthur, he was living in a motel in Knoxville, Tenn. Such accommodations have been his home so routinely that he has learned to travel with a high-watt light bulb in a lens case to assure better illumination for reading and writing. In 1982 he bought a tiny, whitewashed stone cottage behind a shopping center in El Paso. But he wouldn't take me inside. Renovation, which began a few years ago, has stopped for lack of funds. "It's barely habitable," he says. He cuts his own hair, eats his meals off a hot plate or in cafeterias and does his wash at the Laundromat.

McCarthy estimates that he owns about 7,000 books, nearly all of them in storage lockers. "He has more intellectual interests than anyone I've ever met," says the director Richard Pearce, who tracked down McCarthy in 1974 and remains one of his few "artistic" friends. Pearce asked him to write the screenplay for "The Gardener's Son," a television drama about the murder of a South Carolina mill owner in the 1870's by a disturbed boy with a wooden leg. In typical McCarthy style, the amputation of the boy's leg and his slow execution by hanging are the moments from the show that linger in the mind.

McCarthy has never shown interest in a steady job, a trait that seems to have annoyed both his ex-wives. "We lived in total poverty," says the second, Annie DeLisle, now a restaurateur in Florida. For nearly eight years they lived in a dairy barn outside Knoxville. "We were bathing in the lake," she says with some nostalgia. "Someone would call up and offer him $2,000 to come speak at a university about his books. And he would tell them that everything he had to say was there on the page. So we would eat beans for another week."

McCarthy would rather talk about rattlesnakes, molecular computers, country music, Wittgenstein -- anything -- than himself or his books. "Of all the subjects I'm interested in, it would be extremely difficult to find one I wasn't," he growls. "Writing is way, way down at the bottom of the list."

His hostility to the literary world seems both genuine ("teaching writing is a hustle") and a tactic to screen out distractions. At the MacArthur reunions he spends his time with scientists, like the physicist Murray Gell-Mann and the whale biologist Roger Payne, rather than other writers. One of the few he acknowledges having known at all was the novelist and ecological crusader Edward Abbey. Shortly before Abbey's death in 1989, they discussed a covert operation to reintroduce the wolf to southern Arizona.

McCarthy's silence about himself has spawned a host of legends about his background and whereabouts. Esquire magazine recently printed a list of rumors, including one that had him living under an oil derrick. For many years the sum of hard-core information about his early life could be found in an author's note to his first novel, "The Orchard Keeper," published in 1965. It stated that he was born in Rhode Island in 1933; grew up outside Knoxville; attended parochial schools; entered the University of Tennessee, which he dropped out of; joined the Air Force in 1953 for four years; returned to the university, which he dropped out of again, and began to write novels in 1959. Add the publication dates of his books and awards, the marriages and divorces, a son born in 1962 and the move to the Southwest in 1974, and the relevant facts of his biography are complete.

The oldest son of an eminent lawyer, formerly with the Tennessee Valley Authority, McCarthy is Charles Jr., with five brothers and sisters. Cormac, the Gaelic equivalent of Charles, was an old family nickname bestowed on his father by Irish aunts.

It seems to have been a comfortable upbringing that bears no resemblance to the wretched lives of his characters. The large white house of his youth had acreage and woods nearby, and was staffed with maids. "We were considered rich because all the people around us were living in one- or two-room shacks," he says. What went on in these shacks, and in Knoxville's nether world, seems to have fueled his imagination more than anything that happened inside his own family. Only his novel "Suttree," which has a paralyzing father-son conflict, seems strongly autobiographical.

"I was not what they had in mind," McCarthy says of childhood discord with his parents. "I felt early on I wasn't going to be a respectable citizen. I hated school from the day I set foot in it." Pressed to explain his sense of alienation, he has an odd moment of heated reflection. "I remember in grammar school the teacher asked if anyone had any hobbies. I was the only one with any hobbies, and I had every hobby there was. There was no hobby I didn't have, name anything, no matter how esoteric, I had found it and dabbled in it. I could have given everyone a hobby and still had 40 or 50 to take home." WRITING AND READING seem to be the only interests that the teen-age McCarthy never considered. Not until he was about 23, during his second quarrel with schooling, did he discover literature. To kill the tedium of the Air Force, which sent him to Alaska, he began reading in the barracks. "I read a lot of books very quickly," he says, vague about his self-administered syllabus.

McCarthy's style owes much to Faulkner's -- in its recondite vocabulary, punctuation, portentous rhetoric, use of dialect and concrete sense of the world -- a debt McCarthy doesn't dispute. "The ugly fact is books are made out of books," he says. "The novel depends for its life on the novels that have been written." His list of those whom he calls the "good writers" -- Melville, Dostoyevsky, Faulkner -- precludes anyone who doesn't "deal with issues of life and death." Proust and Henry James don't make the cut. "I don't understand them," he says. "To me, that's not literature. A lot of writers who are considered good I consider strange."

"The Orchard Keeper," however Faulknerian in its themes, characters, language and structure, is no pastiche. The story of a boy and two old men who weave in and out of his young life, it has a gnarliness and a gloom all its own. Set in the hill country of Tennessee, the allusive narrative memorializes, without a trace of sentimentality, a vanishing way of life in the woods. An affection for coon hounds binds the fate of the characters, who wander unaware of any kinship. The boy never learns that a decomposing body he sees in a leafy pit may be his father.

McCarthy began the book in college and finished it in Chicago, where he worked part time in an auto-parts warehouse. "I never had any doubts about my abilities," he says. "I knew I could write. I just had to figure out how to eat while doing this." In 1961 he married Lee Holleman, whom he had met at college; they had a son, Cullen (now an architecture student at Princeton), and quickly divorced, the yet-unpublished writer taking off for Asheville, N.C., and New Orleans. Asked if he had ever paid alimony, McCarthy snorts. "With what?" He recalls his expulsion from a $40-a-month room in the French Quarter for nonpayment of rent.

After three years of writing, he packed off the manuscript to Random House -- "it was the only publisher I had heard of." Eventually it reached the desk of the legendary Albert Erskine, who had been Faulkner's last editor as well as the sponsor for "Under the Volcano" by Malcolm Lowry and "The Invisible Man" by Ralph Ellison. Erskine recognized McCarthy as a writer of the same caliber and, in the sort of relationship that scarcely exists anymore in American publishing, edited him for the next 20 years. "There is a father-son feeling," says Erskine, despite the fact, as he sheepishly admits, that "we never sold any of his books."

For years McCarthy seems to have subsisted on awards money he earned for "The Orchard Keeper" -- including grants from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the William Faulkner Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation. Some of these funds went toward a trip to Europe in 1967, where he met DeLisle, an English pop singer, who became his second wife. They settled for many months on the island of Ibiza in the Mediterranean, where he wrote "Outer Dark," published in 1968, a twisted Nativity story about a girl's search for her baby, the product of incest with her brother. At the end of their independent wanderings through the rural South the brother witnesses, in one of McCarthy's most appalling scenes, the death of his child at the hands of three mysterious killers around a campfire: "Holme saw the blade wink in the light like a long cat's eye slant and malevolent and a dark smile erupted on the child's throat and went all broken down the front of it. The child made no sound. It hung there with its one eye glazing over like a wet stone and the black blood pumping down its naked belly."

"Child of God," published in 1973 after he and DeLisle returned to Tennessee, tested new extremes. The main character, Lester Ballard -- a mass murderer and necrophiliac -- lives with his victims in a series of underground caves. He is based on newspaper reports of such a figure in Sevier County, Tenn. Somehow, McCarthy finds compassion for and humor in Ballard, while never asking the reader to forgive his crimes. No social or psychological theory is offered that might explain him away.

In a long review of the book in The New Yorker, Robert Coles called McCarthy a "novelist of religious feeling," comparing him with the Greek dramatists and medieval moralists. And in a prescient observation he noted the novelist's "stubborn refusal to bend his writing to the literary and intellectual demands of our era," calling him a writer "whose fate is to be relatively unknown and often misinterpreted."

"Most of my friends from those days are dead," McCarthy says. We are sitting in a bar in Juarez, discussing "Suttree," his longest, funniest book, a celebration of the crazies and ne'er-do-wells he knew in Knoxville's dirty bars and poolrooms. McCarthy doesn't drink anymore -- he quit 16 years ago in El Paso, with one of his young girlfriends -- and "Suttree" reads like a farewell to that life. "The friends I do have are simply those who quit drinking," he says. "If there is an occupational hazard to writing, it's drinking."

Written over about 20 years and published in 1979, "Suttree" has a sensitive and mature protagonist, unlike any other in McCarthy's work, who ekes out a living on a houseboat, fishing in the polluted city river, in defiance of his stern, successful father. A literary conceit -- part Stephen Daedalus, part Prince Hal -- he is also McCarthy, the willful outcast. Many of the brawlers and drunkards in the book are his former real-life companions. "I was always attracted to people who enjoyed a perilous life style," he says. Residents of the city are said to compete to find themselves in the text, which has displaced "A Death in the Family" by James Agee as Knoxville's novel.

McCarthy began "Blood Meridian" after he had moved to the Southwest, without DeLisle. "He always thought he would write the great American western," says a still-smarting DeLisle, who typed "Suttree" for him -- "twice, all 800 pages." Against all odds, they remain friends. If "Suttree" strives to be "Ulysses," "Blood Meridian" has distinct echoes of "Moby-Dick," McCarthy's favorite book. A mad hairless giant named Judge Holden makes florid speeches not unlike Captain Ahab's. Based on historical events in the Southwest in 1849-50 (McCarthy learned Spanish to research it), the book follows the life of a mythic character called "the kid" as he rides around with John Glanton, who was the leader of a ferocious gang of scalp hunters. The collision between the inflated prose of the 19th-century novel and nasty reality gives "Blood Meridian" its strange, hellish character. It may be the bloodiest book since "The Iliad."

"I've always been interested in the Southwest," McCarthy says blandly. "There isn't a place in the world you can go where they don't know about cowboys and Indians and the myth of the West."

More profoundly, the book explores the nature of evil and the allure of violence. Page after page, it presents the regular, and often senseless, slaughter that went on among white, Hispanic and Indian groups. There are no heroes in this vision of the American frontier.

"There's no such thing as life without bloodshed," McCarthy says philosophically. "I think the notion that the species can be improved in some way, that everyone could live in harmony, is a really dangerous idea. Those who are afflicted with this notion are the first ones to give up their souls, their freedom. Your desire that it be that way will enslave you and make your life vacuous."

This tooth-and-claw view of reality would seem not to accept the largesse of philanthropies. Then again, McCarthy is no typical reactionary. Like Flannery O'Conner, he sides with the misfits and anachronisms of modern life against "progress." His play, "The Stonemason," written a few years ago and scheduled to be performed this fall at the Arena Stage in Washington, is based on a Southern black family he worked with for many months. The breakdown of the family in the play mirrors the recent disappearance of stoneworking as a craft.

"Stacking up stone is the oldest trade there is," he says, sipping a Coke. "Not even prostitution can come close to its antiquity. It's older than anything, older than fire. And in the last 50 years, with hydraulic cement, it's vanishing. I find that rather interesting."

By comparison with the sonority and carnage of "Blood Meridian," the world of "All the Pretty Horses" is less risky -- repressed but sane. The main character, a teen-ager named John Grady Cole, leaves his home in West Texas in 1949 after the death of his grandfather and during his parents' divorce, convincing his friend Lacey Rawlins they should ride off to Mexico.

Dialogue rather than description predominates, and the comical exchanges between the young men have a bleak music, as though their words had been whittled down by the wind off the desert:

They rode. You ever get ill at ease? said Rawlins. About what? I dont know. About anything. Just ill at ease. Sometimes. If you're someplace you aint supposed to be I guess you'd be ill at ease. Should be anyways. Well suppose you were ill at ease and didnt know why. Would that mean that you might be someplace you wasn't supposed to be and didnt know it? What the hell's wrong with you? I dont know. Nothin. I believe I'll sing. He did.

A linear tale of boyish episodes -- they meet vaqueros, are joined by a hapless companion, break horses on a hacienda and are thrown in jail -- the book has a sustained innocence and a lucidity new in McCarthy's work. There is even a budding love story.

"You haven't come to the end yet," says McCarthy, when asked about the low body count. "This may be nothing but a snare and a delusion to draw you in, thinking that all will be well."

The book is, in fact, the first volume of a trilogy; the third part has existed for more than 10 years as a screenplay. He and Richard Pearce have come close to making the film -- Sean Penn was interested -- but producers always became skittish about the plot, which has as its central relationship John Grady Cole's love for a teen-age Mexican prostitute.

Knopf is revving up the publicity engines for a campaign that they hope will bring McCarthy his overdue recognition. Vintage will reissue "Suttree" and "Blood Meridian" next month, and the rest of his work shortly thereafter. McCarthy, however, won't be making the book-signing circuit. During my visit he was at work in the mornings on Volume 2 of the trilogy, which will require another extended trip through Mexico.

"The great thing about Cormac is that he's in no rush," Pearce says. "He is absolutely at peace with his own rhythms and has complete confidence in his own powers."

In a pool hall one afternoon, a loud and youthful establishment in one of El Paso's ubiquitous malls, McCarthy ignores the video games and rock-and-roll and patiently runs out the table. A skillful player, he was a member of a team at this place, an incongruous setting for a man of his conservative demeanor. But more than one of his friends describes McCarthy as a "chameleon, able to adjust easily to any surroundings and company because he seems so secure in what he will and will not do."

"Everything's interesting," McCarthy says. "I don't think I've been bored in 50 years. I've forgotten what it was like."

He bangs away in his stone house or in motels on an Olivetti manual. "It's a messy business," he says about his novel-building. "You wind up with shoe boxes of scrap paper." He likes computers. "But not to write on." That's about all he will discuss about his process of writing. Who types his final drafts now he doesn't say.

Having saved enough money to leave El Paso, McCarthy may take off again soon, probably for several years in Spain. His son, with whom he has lately re-established a strong bond, is to be married there this year. "Three moves is as good as a fire," he says in praise of homelessness.

The psychic cost of such an independent life, to himself and others, is tough to gauge. Aware that gifted American writers don't have to endure the kind of neglect and hardship that have been his, McCarthy has chosen to be hardheaded about the terms of his success. As he commemorates what is passing from memory -- the lore, people and language of a pre-modern age -- he seems immensely proud to be the kind of writer who has almost ceased to exist.